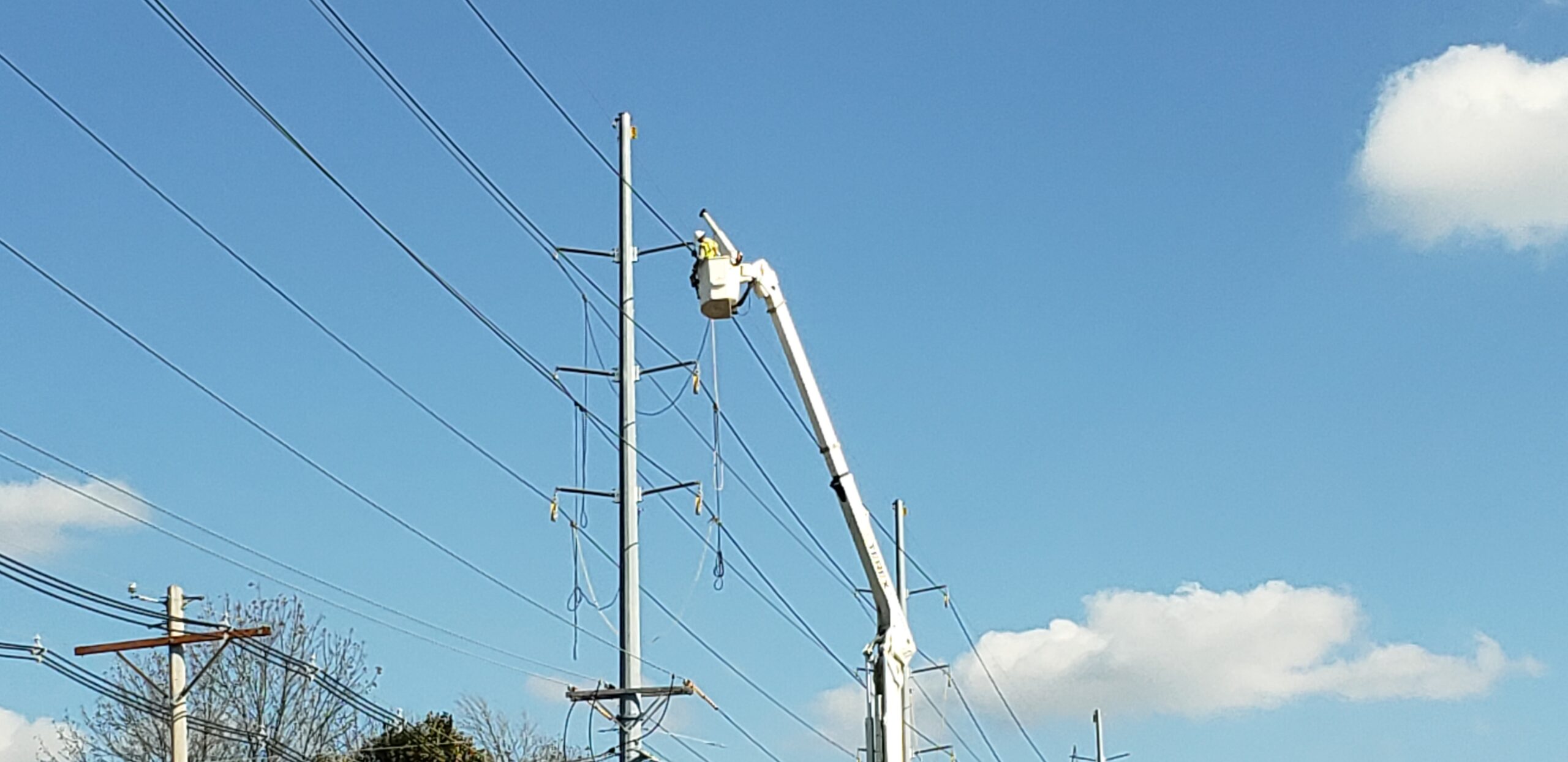

In Part 3 of our article series for electric utility grounding, we’ll be covering the topics of induced voltages and the use of temporary protective grounding (TPG) for systems energized at less than 600 volts.

Secondary Considerations or Primary Hazard – Induced Voltage

There are two types of electric induction: electric field induction (capacitive coupling) and magnetic induction (inductive coupling). While the latter is the more hazardous of the two, they both need to be accounted for and are often present simultaneously under the general term of electromagnetic field/coupling.

Electromagnetic coupling can be defined as the presence of both electric and magnetic fields, generating a circulating current between the grounded sides of a line, often due to the proximity of an adjacent or nearby energized line.

As briefly discussed in Part 2, induction from an adjacent or parallel line or equipment that has been deenergized may not exist at that point in time, but great care must be exercised so that the lines or equipment remain fully deenergized.

Inside the Power Plant

This is especially true inside power plants where medium and high voltage lines or rigid bus segments are installed overhead in open air, or where cables are run together in a common raceway, such as cable trays, duct banks, etc., to feed various large load equipment such as polyphase motors.

For example, if motor number one is taken down for routine maintenance with its feeder circuit number one deenergized while motor number two remains operational (but not running), then no induction will be present. However, if motor number two is started for any reason, then induction will be present.

How Much Induction?

The amount of induction will be dependent on many variables, such as the magnitude of the in-rush and running current, the type of cables used (shielded or unshielded), the proximity of the deenergized cables to the energized cables, etc. All of these possibilities must be carefully examined, considered, and accounted for before making the decision that temporary protective grounding is not needed because of the possible false assumption that “no induction is present” at a particular point in time.

OSHA Considerations

According to Appendix C of 1910.269 – “Protection From Hazardous Differences in Electric Potential,” there are two important conditions the employer must carefully consider for induced voltages when determining whether or not to apply temporary protective grounding after taking all the other necessary precautions.

First, if the employee can be injured through an involuntary reaction, such as falling after receiving an electric shock from an induced voltage that is limited in duration, then a hazard exists if the induced voltage is sufficient to pass a current of 1 mA through a 500-ohm resistor.

While some standards, such as IEEE 1048-2016 – IEEE Guide for Protective Grounding of Power Lines, place the “equivalent worker body resistance” (formerly “total body resistance”) at 1k ohms for the body’s current limits, OSHA and some utilities use the body’s internal resistance level of 500 ohms as a more conservative demarcation point. This is because factors such as breaks in the worker’s skin from cuts, abrasions, or blisters, and/or wetness can substantially reduce skin resistance to near zero ohms.

The second condition mentioned in the Appendix is whether the induced electric shock is unlimited or can be sustained. If either condition is the case (unlimited or sustained), then a hazard exists if the resultant current would be more than 6 mA (≥ 7mA) without any mention of resistance.

The lack of a resistance value makes condition two a more challenging parameter to meet. Technically speaking, any induced voltage that can generate 7 mA or more of current through even a 1-ohm-or-less resistor must be considered hazardous.

As seen, OSHA places very stringent and conservative criteria in the range of milliamps to determine when a hazard exists from induced voltages if TPGs are not used. These criteria are founded on the possibility of current flowing through the worker’s body as mentioned above. If a determination is made that an induction hazard exists, then TPGs must be installed as a mitigation action.

Therefore, before deciding that temporary protective grounding is not necessary because no or “very little” induction is present, all of these contributing factors must be carefully weighed. Workers’ lives are literally at risk.

Temporary Protective Grounding at ≤ 600 Volts

The next topic to consider is the voltage threshold at which temporary protective grounding is mandatory. As discussed in Part 1, most electric utility companies establish the demarcation voltage at 600 volts or more. However, neither OSHA 1910.269(n), subpart S for general industry, nor 1926.962 subpart V for construction specify a voltage level when TPGs are required for electric generation, transmission and distribution (note that 1926 subpart V does not cover generation).

Many readers will find it somewhat revelatory that the only reference to voltage, as it applies to temporary protective grounding, is limited to the method used to apply and remove the grounds through either a live-line-tool also known as a “hotstick” or insulating equipment. Over the 600V threshold, live-line-tools must be used to attach and remove TPGs. However, at or below the 600V level, insulating equipment is permitted during installation and removal. The permissive directives pursuant to 1910.269(n)(6)(i) through (6)(ii) and 1926.962(f)(1) through (f)(2) are listed below.

1910.269(n)(6)(i) and 1926.962(f)(1)

Order of Connection. The employer shall ensure that, when an employee attaches a ground to a line or to equipment, the employee attaches the ground-end connection first and then attaches the other end by means of a live-line tool. For lines or equipment operating at 600 volts or less, the employer may permit the employee to use insulating equipment other than a live-line tool if the employer ensures that the line or equipment is not energized at the time the ground is connected or if the employer can demonstrate that each employee is protected from hazards that may develop if the line or equipment is energized. (emphasis added)

1910.269(n)(6)(ii) and 1926.962(f)(2)

Order of Removal. The employer shall ensure that, when an employee removes a ground, the employee removes the grounding device from the line or equipment using a live-line tool before he or she removes the ground-end connection. For lines or equipment operating at 600 volts or less, the employer may permit the employee to use insulating equipment other than a live-line tool if the employer ensures that the line or equipment is not energized at the time the ground is disconnected or if the employer can demonstrate that each employee is protected from hazards that may develop if the line or equipment is energized. (emphasis added)

If the line or equipment is energized at 600 volts or less, then the worker is permitted to use “insulating equipment” (most interpret this as rubber insulating gloves with leather protectors) to attach or remove the TPG from the “other end,” meaning the normally energized part(s) that are deenergized and under the control of the applicable hazardous energy procedure. This can be LOTO for generation per 1910.269(d), or clearance orders per 1910.2690(m) and 1926.961 (T&D systems).

What to Expect in Part 4

Keep in mind that using TPGs at low voltages (<600 volts) can pose challenges with respect to the proper sizing due to the extremely high fault currents commonly found in large low voltage systems according to 1910.269(n)(4)(i).

In Part 4, we’ll cover some of the specific challenges and considerations when using TPGs with lines and equipment energized at 600 volts or less.

Ken, thanks for the excellent information you provided to help us navigate this difficult topic. I’m curious about OSHA’s stance on using insulating equipment (rather than live-line tools) when applying temporary protective grounds (TPGs) to voltages of 600 volts or less.

OSHA’s 1999 letter of interpretation (Standard Interpretations / 1910.269: Application of personal protective grounds for employee protection) states that insulating tools are necessary to keep employees at a safe distance when installing or removing grounds, due to the heat generated by arc flash. This suggests that distance is a key factor in arc flash protection.

However, I’m puzzled that 480-volt systems can produce higher incident energy than 4,160-volt systems. Could you help me understand what I’m missing here? I want to make sure I have a complete grasp of OSHA’s requirements and the underlying safety principles.

Thank you again for the excellent information you provided.